Students occupying Columbia Unversity in April 1968 (Photo from Who Rules Columbia?, North American Congress on Latin America records, Tamiment Library, NYU)

Fifty-five years ago, an explosive 34-page pamphlet titled Who Rules Columbia? was published. It’s not remembered by many people today – but it should be. The pamphlet came out just weeks after the historic 1968 student uprising at Columbia University. It brought a sharp power analysis that dissected and mapped out Columbia as a member of the corporate power structure interlocked with war, racism, finance and real estate. In doing so, it offered a fresh analysis and strategic direction to the student movement at Columbia and beyond.

The 1968 Columbia student strike was one of the most iconic events of the U.S. campus student movement of the 1960s and 1970s. For a week at the end of April, hundreds of students occupied five buildings and paralyzed the campus. They demanded that the university end a racist expansion project into a nearby public park and sever ties with the U.S. war and intelligence machine. More broadly, it was also a protest for a different kind of university – one less captured by elite interests, one more democratic and more accountable, one more aligned with values of equality and justice.

What’s less known about the high drama at Columbia is that – amid the uprising and shortly after – a small and plucky group of power researchers worked day and night to put together a stunning analysis that laid bare the corporate-aligned power structure at the core of Columbia’s governance. Who Rules Columbia? showed in painstaking detail how the university’s “rulers” were fully enmeshed within the heights of U.S. capitalism and empire and how these ties shaped everything about the university, from its finances to its academics. In an edgy and accessible way, Who Rules Columbia? connected the dots and illustrated the networks of corporate and militarist power at the university.

“Who Rules Columbia? had an enormous impact,” Mike Locker, one of the pamplet’s co-authors, told LittleSis. “We crystallized how people thought about Columbia University, as a capitalist institution, and not as a school of learning. This was a place to turn out people for the system, to train them to be effective agents of corporate power.”

Today, as organizers across the U.S. wage campaigns aimed at big universities – whether around fossil fuel divestment, workers’ rights, or disbanding private police forces – Who Rules Columbia? serves as a shining model of how power research can support and strengthen organizing efforts.

* * *

A few developments created the conditions for the 1968 Columbia student strike and the publication of Who Rules Columbia?

One was the rise of a broad student movement on U.S. campuses during the 1960s that was critical of the power of universities and the role they played in supporting racist, militarist and pro-corporate power structures. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), one of the largest New Left groups of the era, was a major expression of this. In its founding document, SDS lambasted the Cold War-era U.S. university as a faceless and bureaucratic apparatus that aimed to produce, assembly line-style, a docile and conformist workforce for corporate America and its global empire. This critique burst onto the national scene during the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement, where activist Mario Savio famously analogized the University of California system to an odious machine grinding down its students into obedient pieces.

Another huge factor was the U.S. war on Vietnam. By 1968, over a half-million US troops were in Vietnam, and the biggest antiwar movement in U.S. history was reaching its heights. This was one of the defining causes for the generation of radicalized students spread across the nation’s campuses in the late 1960s. To thousands upon thousands of them, the war was not merely unjust, but intolerable, and many of these students saw their own colleges and universities as complicit in U.S. crimes being committed in southeast Asia.

Another defining cause for this generation was the battle to dismantle Jim Crow both north and south. Many 1960s college organizers were radicalized by the civil rights movements and cut their organizing teeth with groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). By the late 1960s, with Black Power and groups like the Blank Panthers ascendant, many Black student activists – like those in Columbia’s Student Afro-American Society (SAS) – increasingly saw universities as having a colonial relationship to their surrounding Black and Brown and poor and working-class communities.

All this swelled up and converged with other events in 1968, a truly world-historic year where revolt encompassed the globe. The U.S. saw two major assassinations, Martin Luther King Jr in April and Bobby Kennedy in June, while Lyndon B. Johnson, the most ambitious US politician in a generation, bowed out of politics in the face of mounting crisis. Then in August, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago turned into a civil war as cops smashed the heads of protestors on national television. The year ended with Tommie Smith and John Carlos defiantly thrusting their fists in the air during the U.S. national anthem at the Olympics in Mexico City in solidarity with oppressed people worldwide.

* * *

The Columbia University student uprising of April 1968 was a key event in this chain of insurgency. Going into 1968, protests on campus had been building up around two big issues. One was connected to the war and militarism, and specifically Columbia’s ties to the military-industrial complex and military recruitment on campus. The other was Columbia’s plan to build a gymnasium on public land in nearby Morningside Park, which was viewed by many as a racist land grab by an elite private university, particularly because the gym would be for the almost exclusive youth of mostly white students with a separate, basement-level entrance for Harlem residents who were mostly Black and Brown people.

Going into early 1968, the Tet Offensive – a military surge by Vietnamese national liberation forces against the U.S. that proved to be a turning point in the war – and King’s assassination only intensified the polarized climate. Protests against the gymnasium and the university’s ties to the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a research arm that supported U.S. militarism, escalated, and on Tuesday, April 23, 1968, hundreds of students gathered at the center of campus. Leaders from Students for a Democratic Society and the Student Afro-American Society gave speeches and a sit-in and occupation of Hamilton Hall ensued, which soon spread to four other buildings.

For the next week, hundreds of students barricaded themselves in the five buildings demanding that the construction of the Columbia gym be stopped and that the university sever all ties to the IDA. The nation was riveted by the event: one of the country’s elite universities had been taken over by its students and shut down. Some occupiers broke into secret files in President Grayson Kirk’s office that testified to many of their suspicions about the school’s ties to the war and military. The separate building occupations had different groups of students and protest strategies, but stayed connected through a Strike Coordinating Committee.

On April 30, a week after the strike began, hundreds of police moved in to break up the occupation. Telephone and water lines to the five buildings were cut off. The police were absolutely brutal, smashing heads with flashlights and blackjacks. Over 700 people, mostly students, were arrested. They were dragged out in the middle of the might.

* * *

The writing and production of Who Rules Columbia? occurred during this high drama, and the pamphlet was released around a month after the uprising was repressed. It was produced by a small band of researchers who were part of the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA), which had been founded in 1966. NACLA’s mission was largely focused on exposing the corporate interests driving U.S. imperialism in Latin America. Its members had been influenced by the radical sociologist and Columbia professor C. Wright Mills, who showed his young followers how to analyze and critique corporate power through his classic 1956 book The Power Elite before his untimely death in 1962.

Throughout the late 1960s NACLA published numerous exposés of U.S. business interests in Latin America as well as research methodology guides for activists. NACLA wasn’t interested in doing research for merely academic purposes – they wanted to provide concrete support and solidarity for the fight against U.S. imperialism in Latin America.

One of NACLA’s members, Michael Klare, was a graduate student at Columbia in 1968, and the group coincidentally landed office space right next to the heart of Columbia’s campus. NACLA members had done some research on the Columbia power structure, and they knew how to research it further – what libraries to visit, what journals to read, and what documents to consult.

When the strike hit, NACLA went into action. “There was no internet and no computers,” remembered Klare, “so this meant digging into libraries.” They scoured sources like Standard & Poor’s Directory and Who’s Who in America? and newspapers like the New York Times and the financial press. They read corporate disclosures and dusty minutes of Trustee meetings. They scanned Pentagon journals and the Army R&D Newsletter, which listed research contracts for the war. Locker would later say:

We wanted to challenge power at its core, and knew that the most efficient way of doing this was by understanding it, which meant rigorous documentation, and then giving people all the facts so they could continue their own investigations and take action.

The group divided the research labor. Some dug into Columbia’s connections to the military and intelligence community while others looked at its real estate and Wall Street ties. They worked day and night in a stuffy room with no air conditioning but with a burning passion and inspiration. “Nobody funded Who Rules Columbia?,” Locker recalled. “We lived like church mice. But the motivational forces were really there, and there were tremendous juices of creativity that came out of that.” Klare told LittleSis:

There was a sense that this was one of the events of our lives. The Columbia strike was an earthquake. It’s hard to describe to people today. There had been nothing like it on any American campus up until that point – where you had hundreds of tactical police cracking down on the university, arresting hundreds and hundreds of students, beating them, elite Ivy League university, and then the campus being shut down.

The researchers typed up their findings on a Selectric IBM typewriter. Klare, who had gone to art school and architecture school and knew how to do the layout, cut and paste text and images onto a drafting board.

“We knew that graduation was coming up and that there’d be a lot of people on campus,” said Klare, “and we wanted to have it ready for that date.” They did, and hundreds of students who streamed out the 116th and Broadway subway station gobbled up copies.

* * *

Who Rules Columbia? mapped out the wealthy, well-connected men who sat on the school’s Board of Trustees. It brought to light the corporate and militarist interests they represented and the networks and institutions through which they wielded power and influence. The pamphlet did not just aim to put a spotlight on power for transparency’s sake. Rather, it aimed to diagnose the university’s core power structure and its inner-workings that generated the issues that were flashpoints of student discontent in the first place – all so that the movement, including protesters at Columbia, could more effectively strategize and organize around those sources of power.

Far from an idyllic place where the life of the mind roamed free, the pamphlet declared that the university existed “to service outside interests which, by controlling Columbia’s finances, effectively control its policy.” These “outside interests” were represented on the Board of Trustees and “organized the university as a “factory” to produce the skilled technicians and management personnel the U.S. industrial and defense apparatus needs.”

In other words, the university was a vehicle for money and power, and this shaped everything about it that students disliked: its hierarchies, land grabs, stifled learning environment, and unaccountable administrators. This university was precisely designed this way to reflect the interest of its trustees whose rule over the university and its finances was shaped by their outside connections to the world of elite power, corporate profits, and war-making.

This was “the crucial issue behind the student rebellion,” said Who Rules Columbia? – the control of the university by outside corporate forces that didn’t prioritize the students and community or the mission of learning. Everything the students were protesting at Columbia grew out of this power structure and the interests and people that composed it.

* * *

But what were these interests and who were these powerful people? For nearly three dozen pages the pamphlet analyzed and mapped out the main power blocs – especially real estate, militarism, and finance – among the trustees that sat atop the university. Who Rules Columbia? is filled with page after page of analysis, connections, details, sources, lists and maps that name names and connect dots.

It documented how the development and growth of the university into the 20th century was bound up with the expansion of U.S. corporate power and empire that looked to Columbia to help service its needs and profits. Much space was devoted to exposing Columbia’s “real estate establishment” and how developers and realtors with an interest in profiting from university properties and expansion were attracted to the board.

For example, the pamphlet profiled Percy Uris, co-founder of Uris Buildings Corporation, a huge NYC real estate company. Uris was appointed a lifetime trustee of Columbia in 1960, and the pamphlet argued that he used his contacts and power on the board as chair of its finance committee “to assemble sites which his company then leased from Columbia” and “to attain not only tenants and creditors but also top-notch legal and financial advice.”

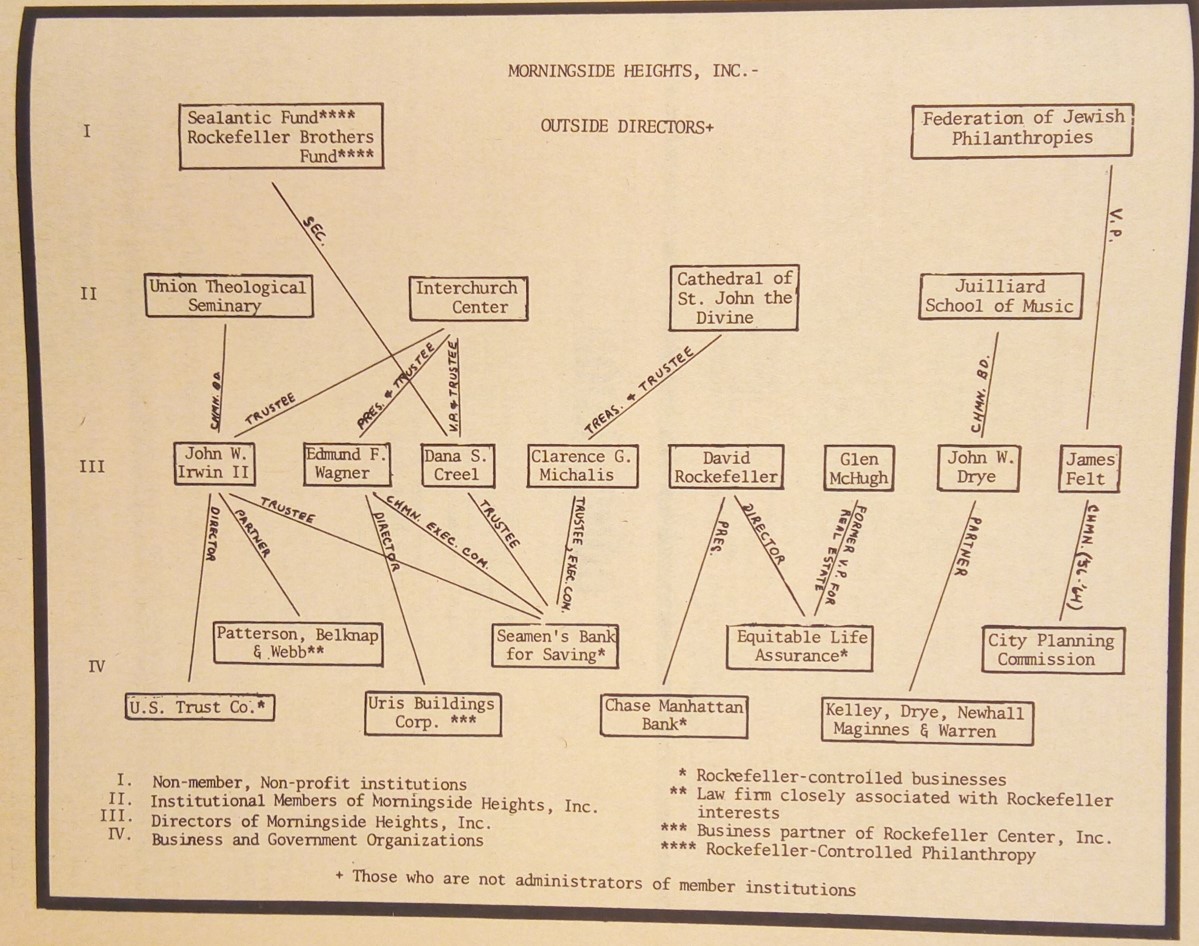

Who Rules Columbia? also mapped out the corporate interests tied to the university’s expansion within Morningside Heights and – often using colonial language and analogies – the ways that it “redeveloped” the surrounding community. The interests of the Rockefeller family featured prominently here, as they did in the discussion of Uris’s influence on the board. Who Rules Columbia? also included an appendix with all the university’s properties.

“They were real players in the real estate world,” said Locker. “And the board and the finances of the school reflected that.”

Another major focus of the pamphlet was on Columbia’s ties to war and militarism. It explored how Columbia aided the administering of the U.S. empire through corporate ties and research support. It mapped out the trustees’ enmeshment with “the foreign policy establishment,” specifically with entities like the Asia Foundation, the Council of Foreign Relations, and the CIA.

A whole section was devoted to showing how Columbia’s trustees were intertwined with its School of International Affairs (SIA) that primarily existed, the pamphlet argued, to serve U.S. foreign policy and global business interests. “The purpose of the SIA,” the pamphlet said, “has never been in doubt: to train experts in international affairs and foreign areas for administration positions in America’s expanding overseas empire.”

Who Rules Columbia? also named specific services and study areas that the SIA provided for U.S. foreign power and connected the interests of trustees’ to this Cold War foreign policy establishment. It mapped out the ties between CIA-linked organizations and powerful people at Columbia. In its section on the “Defense-Research Nexus” and the “Columbia University Defense Establishment,” the pamphlet listed the different ways Columbia research was aiding U.S. foreign policy through military and scientific research that was sponsored by the Department of Defense and CIA.

The pamphlet also included a folded insert chart called “The Top 22: Columbia’s Ruling Elite” that mapped out the corporations and government entities each trustee was tied to, including Wall Street banks, defense manufacturers, oil companies, real estate developers, mass media, utilities and the Pentagon. Locker recalled:

It was exactly as C. Wright Mills had laid out in his book The Power Elite. Columbia turned out to be fully integrated into the corporate world, even though it had a thoroughly liberal façade. We set out to reveal to students the framework of their university from a wholly new angle, to show them where the levers of power at Columbia really were. After all, you can’t challenge the power base of an institution if you don’t know precisely who owns what.

Through the corporate power structure analysis, Who Rules Columbia? connected the dots and argued that the different fights at the university grew out of the same dynamic. While the fight against the IDA and the Morningside Park Gym “seemed separate,” the pamphlet confluded, “they were ineradically [sic] fused,” with “each representing different aspects of property and property drives,” whether that be empire abroad or colonial-style expansion at home.

Maybe most of all, Who Rules Columbia? showed that the university was something other than it claimed to be; not a utopian space for pure learning, but a corporate-aligned power structure enabling war and racism, overseen by a small cohort of powerful and influential corporate elites who were upholding and profiting from empire at home and abroad. The university was a hierarchical power structure with trustees who were the “rulers.” The student strike and occupation aimed for a democratic “redistribution of power” by the “ruled” against the campus’s “illegitimate authority.” A different university was possible if that power structure was challenged.

* * *

Who Rules Columbia? had an immediate impact at Columbia and beyond. Remembering events forty years later in 2008, Juan González, the longtime journalist and co-host of Democracy Now!, and a leader of the 1968 student strike, recalled that:

[O]ne of the interesting things that came out of the strike is this pamphlet that the students produced in the midst of the strike called “Who Rules Columbia?” And somebody actually just gave me an old copy about a week ago, and I started to read it. And it is really an extraordinary analysis, not only of corporate influence on a university, but also on land policy on the university.

Indeed, Who Rules Columbia? broadened and sharpened the student movement’s analysis of universities as crucial parts of society’s wider corporate power structure. The pamphlet spread and numerous other campuses – from Harvard to Yale to MIT and beyond – produced their own version.

“Dozens of other universities copied that format,” said Locker. “We created the template that other universities used, which led to protests. The notion of identifying the trustees and all of their connections was revelatory – not only at Columbia, but everywhere else.”

One of those other campuses, New York University (NYU), was just downtown from Columbia. Two NYU organizers at the time, Beth Lyons and Stephanie Rugoff, had been doing their own power research into their school in 1967 and 1968. They were members of SDS and knew the NACLA researchers. They shared some of these materials with LittleSis, which you can see here.

The NYU researchers mapped out the university leadership’s ties to corporations like Union Carbide (now part of Dow Chemical) that produced Agent Orange for the U.S. war in Vietnam and was profiting off of South African Apartheid. Lyons described their research in ways that echoed the research that went into the making of Who Rules Columbia? – for example, relying on the business press and Pentagon directories.

“We were as rigorous as we could be,” said Lyons. “We went to the sources of what we were attacking. It was quite labor intensive.” Lyons and Rugoff would distribute leaflets and pamphlets around NYU. “A lot of students got to see them and learned about the various trustees,” said Lyons.

* * *

Who Rules Columbia? should also be seen as another expression of a wider flourishing of corporate power research in the 1960s and into the 1970s, where groups like NACLA, National Action/Research on the Military-Industrial Complex (NARMIC), and the SNCC Research Department, often inspired by the work of scholars like C. Wright Mills and G. William Domhoff, collectively built a tradition of research that organizers and researchers today – like LittleSis and many of our comrades and allies – have inherited.

More broadly, Who Rules Columbia? holds lessons for researchers and organizers in our current moment. It’s a shining example of how power research can support and strengthen social movements, including and especially during moments of heightened protest.

This kind of power analysis is also an antidote to inward-looking campus activism. By understanding universities as key players in the wider corporate power structure, and by mapping out the corporate-aligned rulers of their universities, students can discover all kinds of real-world organizing leverage they have that can recast campus activism in a whole new strategic light. Indeed, some campus campaigns (for example, fossil fuel divestment campaigns at Harvard and Princeton) have been mapping out their trustees in creative ways.

“I think it still is important,” said Rugoff. “The same class of people still controls everything. And it’s useful to know who’s who in the particular university you’re involved in.”

Writing a half-century after the 1968 Columbia student strike, Mike Locker wrote that “power structure research was our way of fighting back” against the crimes the U.S. was committing in Vietnam – and of not being complicit.

“When I look back on the past fifty years,” Locker recalled, “one central theme emerges: power structure research is an essential component for developing an effective strategy to confront injustice and change our broken economic and political system.”