Photo by Ron Cogswell, ‘Change is Brewing!’, Starbucks Workers Union Efforts Courthouse Plaza Arlington (VA), December 2022 (via Flickr)

Big news came in mid-August when Cornell University, one of the most prestigious universities in the U.S., announced that it would not renew its contract with Starbucks after it expires at the end of June 2025 and will stop serving Starbucks at its dining facilities.

Cornell’s decision came in the face of escalating student pressure to ditch Starbucks because of its egregious anti-union activity against Starbucks workers who have built a nationwide unionization campaign at the retail coffee megachain. Cornell is in Ithaca, New York, where Starbucks shut down all of its corporate-operated stores after they unionized. Cornell students, some of whom worked at the shuttered stores, demanded that their school stop doing business with union busters.

Cornell’s move grabbed news headlines, in part, because it signaled a potential new opening and point of leverage for the union drive: campus allies of the union could begin to build campaigns to dislodge Starbucks from their campus. This would not only impact the company’s bottom line, but also represent a PR headache and open the floodgates for campus communities across the nation to concretely support the union campaign. Indeed, similar efforts are underway at other schools, and Starbucks Workers United is helping to facilitate these efforts.

This new development highlights the crucial role that universities and colleges play within the larger corporate structure and the strategic position that campus constituencies like students hold at their institutions. Colleges are more than places where people go to school; they are sites of corporate power, of labor and consumption, and of investment, all of which are intertwined with the wider terrain of capitalism that stretches off campus.

Moreover, if we also think of Starbucks more expansively — not just as embodied in its stores or coffee sales, but as itself a power network with executives, board directors, banks, investors, and attorneys — then the surface area for protesting against campus ties to union-busting suddenly becomes a lot broader and more open to creative research and action.

This primer discusses how different pieces of the Starbucks power network — from the board directors who govern the company, to the banks that help it raise billions in cash, to the “union avoidance” attorneys that it hires — are all over U.S. college campuses. You’ll also find helpful tips on how to research university investments to discover if your college is invested in or doing business with Starbucks (or any corporation, for that matter).

We will see that the Starbucks power network is present at dozens and dozens of universities, from the University of Chicago to NYU, from Central Washington University to UCLA, and many more.

Universities and the Corporate Power Structure

The critique of universities as part of the larger corporate structure is nothing new. In fact, it goes back over a half-century.

In the 1960s, New Left activists developed an analysis of university power as part of a larger corporate bureaucracy that perpetuated war, racism, and poverty. During these years, mass protests erupted at universities across the U.S., with some of the most famous being the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech movement and the 1968 student occupation of Columbia University. In these historic upheavals, students challenged their universities’ involvment in perpetuating the injustices of corporate rule.

In the 1990s and 2000s, campus activism in solidarity with workers spread across the U.S. Students formed coalitions to support farmworkers, garment workers, janitors, and campus workers who labored in dining and laundry facilities. Students fought for living wages for workers at their universities. They campaigned to end their school’s complicity in sweatshop labor that undergirded global supply chains. Many even turned out to support unionizing graduate workers and faculty on their own campus.

All of this organizing and protest was rooted in a shared truth among students: that their university was not an island of learning detached from the rest of society, but rather a crucial node within a larger system of corporate power pitted against poor and working people. Moreover, “corporate power” wasn’t something that existed outside campus, but rather was interlocked with and operating through universities themselves.

One of the most compelling analyses of the university as a corporate power structure was a 1968 pamphlet called Who Rules Columbia? The pamphlet was a product of the historic uprising in April 1968 by Columbia University students against their school’s connections to war and racism. In the pamphlet, the authors carefully showed how the powerful people behind Columbia — its administrators, its big donors, and especially its board of trustees who governed the university — were the same people who stood at the heights of corporate power within society.

The sectors that dominated U.S. capitalism — real estate, the weapons industry, finance, and so on — also ruled over Columbia University. Moreover, these powerful corporate interests used Columbia to network with each other, gain prestige, benefit from research, and acquire investments. In other words, corporate power wasn’t something “out there.” It was right at the heart of the university. And the university, in turn, was a crucial link in the wider chain of the rule of capital.

While Who Rules Columbia? was written over a half-century ago, not much has changed. In fact, corporate domination of universities may be even more entrenched today.

Just take a look at any university board of trustees and you will find it saturated with representatives from Wall Street, real estate, Big Tech, the fossil fuel industry, corporate law firms and consultants, the pharmaceutical industry, and telecommunications giants. And as scholars and journalists have noted, universities today are among the biggest real estate owners and employers in U.S. cities, and their endowments, which as some schools run into the tens of billions, are among Wall Street’s biggest investors.

While all of this may feel a little depressing, there’s a huge silver lining for students at universities who care about things like social justice and workers’ rights: you are primely located within crucial spaces of the corporate power structure, and you can use that strategic position to support important fights happening on and off campus.

Students are at the center of university life. Administrators want to keep them happy. They depend on steady enrollment and want to avoid public controversy. Students can garner a lot of visibility through pickets, building occupations, boycotts, strikes, and other protest actions. They have access to social media networks, student papers, and student governments. From campaigning against their school’s investments in things like fossil fuels and the carceral state, students have recently shown how campaigning around their own university’s concrete ties to larger structures of injustice can make a larger contribution that goes beyond the campus.

As students gain more awareness of their universities as power structures — both in themselves, but also in relationship to the outside corporate world, via people, property and prestige-bestowing — they can think more strategically about that web of power, where they as students sit in it, points of leverage they can hone in on, and how all of this can support larger flights that are happening, including in the labor movement.

Universities and the Starbucks Power Network

The serving of Starbucks coffee products at campus dining facilities and events, as well as the presence of Starbucks stores on campus or around campus, are the most visible ways that the company is present at universities.

Indeed, it’s important to note that Starbucks admits to its own shareholders that it cares a lot about its business operations on college campuses. In its most recent annual report, Starbucks specifically highlights how it locates “company-operated stores” in “high-traffic, high-visibility locations” that prominently include “university campuses.”

In other words, Starbucks really values its campus operations that cater to college communities, and this gives student activists, who have the power to disrupt that arm of its business, a real point of leverage. The news from Cornell proved this.

But Starbucks is also present on campus in other ways that are useful and strategic to know. To more fully map out the ways that Starbucks is on campus, it’s useful to think of the coffee shop mega-chain as a power network with tentacles that go well beyond the likes of Howard Schultz.

From board directors to banks, and law firms to investors, there are a range of corporate actors that drive, permit, and facilitate Starbucks union-busting. Let’s go through these one by one and see examples of how they are present at universities.

Executives and Board Directors

Executives manage day-to-day corporate operations while the Board of Directors manages the governance, oversight, and big decision-making of companies, with hiring and firing power over top executives. For example, Starbucks CEO Laxman Narasimhan is the company’s top executive, but the board of directors — which contains eight members, including Howard Schultz — ultimately hires the CEO and sets their pay. (Narasimhan also sits on the Starbucks board; it’s common for CEOs to have a seat on company boards).

Let’s look at Starbucks’ board members and their ties to universities. Five of seven Starbucks non-CEO directors are trustees at major universities or have other noteworthy ties to universities.

- Satya Nadella is a trustee at the University of Chicago

- Richard E. Allison sits on the board of advisors of the University of North Carolina business school

- Andrew Campion sits on the UCLA business school’s board of advisors.

- Beth Ford sits on an advisory board tied to the Columbia University business school

- Mellody Hobson, who chairs the Starbucks board, sits on the advisory council at Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered AI. Princeton University is also building a college named after Hobson.

We found this information out by looking at the director biographies on Starbucks board page and its most recent proxy statement, and also by searching online with search terms that combine the names of Starbucks directors and words like “trustee,” “university,” and “college.”

Here’s what Starbucks’ board ties to universities looks like mapped out:

There are also connections to universities that Starbucks executives have. For example, Zabrina Jenkins, who holds the influential position of Executive Advisor to the Office of the CEO, is a trustee for Central Washington University.

Starbucks board members also have affiliations to universities through corporations they represent. For example, Starbucks board member Satya Nadella, listed above, is the CEO of Microsoft, and Microsoft has many ties to universities through board seats and corporate partnerships. Student organizers, through research, can go far in mapping out how widely the people and companies that touch Starbucks are present on their campus.

Ultimately, the question comes down to: should universities be bestowing governance positions, and all the prestige that comes with that, to the top executives and directors of a company that’s waging the fiercest anti-union campaign in recent memory?

Banks

Banks are a somewhat hidden actor within the Starbucks power network, but they play a crucial supporting role in the company’s day-to-day operations and its practice of showering billions in stock buybacks and dividends on investors.

Here’s one way this works. Corporations like Starbucks raise billions of dollars in cash by selling off corporate bonds. Basically, when an investor buys corporate bonds from Starbucks, it is lending Starbucks money, and Starbucks promises to pay that money back in a certain number of years, with interest added.

What does Starbucks do with all this cash it raises from selling corporate bonds? S&P Global reported in 2022 that the company intended to use $1.5 billion in bond offerings for “general corporate purposes,” which may include things like “the repurchase of common stock under its ongoing share repurchase program” and “payment of cash dividends on its common stock,” both references to stock buybacks and dividend payouts to investors.

Moreover, while there’s no way to tell for sure, “general corporate purposes” could include one the company’s current major expenses: the huge amount of money it’s paying out in fees to “union avoidance” firms like Littler Mendelson.

In order to sell corporate bonds, companies need banks to serve as middle men that buy their bonds, package them, and sell them off to investors, making a profit through fees and underwriting spreads along the way.

So, who are the banks that are facilitating and profiting from Starbucks corporate operations?

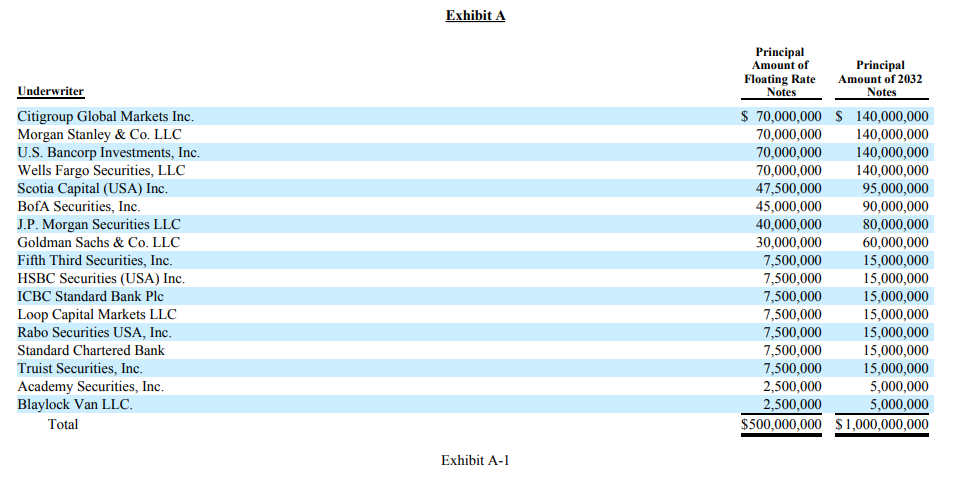

Let’s go back to Starbucks’ recent $1.5 billion corporate bond issuance. Seventeen banks are named as underwriting Starbucks’ bonds. Four of these banks — Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, U.S. Bancorp and Wells Fargo — are underwriting the greatest amounts and are listed as “representatives” of the larger group. The 13 other banks helping Starbucks bring in cash include other prominent consumer-facing banks like Bank of America, J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, and as well as other less recognizable and non-U.S. banks.

Here is a chart from of the official Starbucks company filing on the bond deal that shows how much of the $1.5 billion in bonds each bank is taking on:

Let’s just take one of the most prominent banks here that helps prop up Starbucks: J.P. Morgan, the biggest bank in the U.S.

J.P. Morgan is represented on many university boards. For example, merely searching “J.P. Morgan” with terms like “university,” “college,” and “trustees” shows that executives of this bank are trustees at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Boston College, Smith College, Wells College, and Augustana College, just to name a few.

With numerous major banks helping to finance Starbucks, there’s a very good chance you’ll find at least one of their representatives on your own college’s governing board.

Sticking with J.P. Morgan as an example, you can also scan the biographies of the bank’s executives and board members on the company’s website to find university trustee positions. For example, J.P. Morgan director Alex Gorsky’s bio shows that he’s on the Board of Advisors at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

And here’s a fun fact: remember Mellody Hobson, mentioned above as the independent lead director Starbucks board? Hobson is also on the board of J.P. Morgan. She’s not only personally benefiting from governing Starbucks itself, but also from governing a major bank that profits from helping finance Starbucks.

Banks also provide term loans (ie, one-off loans) and revolving credit agreements (ie, money made available for the company to borrow from if it wants) to Starbucks. You can find documentation of these through digging into the Security and Exchange Commission’s EDGAR database, but you can also find much of this info by doing some creative searching online. For example, combining “Starbucks” with “credit facility” turns up a multi-billion dollar credit facility and names the banks that finance it.

Company Shareholders

While figures like Howard Schultz are huge individual shareholders of Starbucks and remain extremely influential in the company, many of the biggest owners of Starbucks stock are asset management firms and banks, some whom you might recognize and even bank or invest with.

These are massive shareholders of Starbucks who help keep the company afloat by holding onto huge amounts of its stock. They have the power and access to push Starbucks to halt its union-busting, if they chose to use it. Here are the current top ten institutional shareholders of Starbucks common stock according to the business data website Whalewisdom:

| SHAREHOLDER | SHARES HELD | MARKET VALUE | % OWNERSHIP |

| Vanguard Group | 106,504,016 | $10,550,287,826 | 9.2588% |

| Blackrock | 80,373,017 | $7,961,751,019 | 6.9871% |

| State Street Corp | 45,619,709 | $4,519,088,374 | 3.9659% |

| Bank of America | 29,791,379 | $2,951,133,958 | 2.5899% |

| Capital Research Global Investors | 27,368,437 | $2,711,110,954 | 2.3792% |

| Morgan Stanley | 21,940,318 | $2,173,408,280 | 1.9074% |

| Geode Capital Management | 21,952,821 | $2,168,863,447 | 1.9084% |

| Northern Trust Corp | 14,985,721 | $1,484,485,522 | 1.3028% |

| Royal Bank Of Canada | 14,981,868 | $1,484,103,000 | 1.3024% |

| J.P. Morgan Chase | 14,146,699 | $1,401,372,089 | 1.2298% |

Just these ten firms alone hold around one-third of Starbucks stock. The top four — which include the “Big Three” asset managers Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street, as well as Bank of America — own 22.8%. (In addition to the financial services banks provide for corporations discussed above, they also have asset management wings that directly invest in companies).

These big Starbucks shareholders are all over college campuses. Let’s take BlackRock, the second top investor in Starbucks, as an example.

BlackRock is the world’s top asset manager, overseeing around $9.5 trillion in assets. A quick look at BlackRock’s corporate leadership page shows a number of university ties. For example, BlackRock Chairman and CEO Larry Fink sits on the Board of Trustees of New York University, for instance, and BlackRock Chief Legal Officer Christopher J. Meade sits on the Board of Trustees of NYU’s Law School.

Interestingly, in addition to BlackRock being one of the top owners of Starbucks, current Starbucks board member Beth Ford previously served as a board member of BlackRock.

As with other Starbucks power network categories, a much wider map of Starbucks top investors to universities can be developed through research (and this can even be done collaboratively!)

University Investments

Another potential point of leverage for organizers is with university investments. Universities oversee millions and sometimes billions of dollars in endowment money that they seek to grow through investing in stocks, bonds, mutual funds, private equity and hedge funds, real estate, and other investments. Student organizers have a long and proud tradition of campaigning for their universities to divest — pull their money away from — everything from South African apartheid to climate disaster to the prison-industrial complex.

It’s not easy to find out what your university is invested in. Not all universities disclose their specific investments, and many disclosures only contain a small bit of information. Nevertheless, there are some ways you can try to dig into your university’s investments.

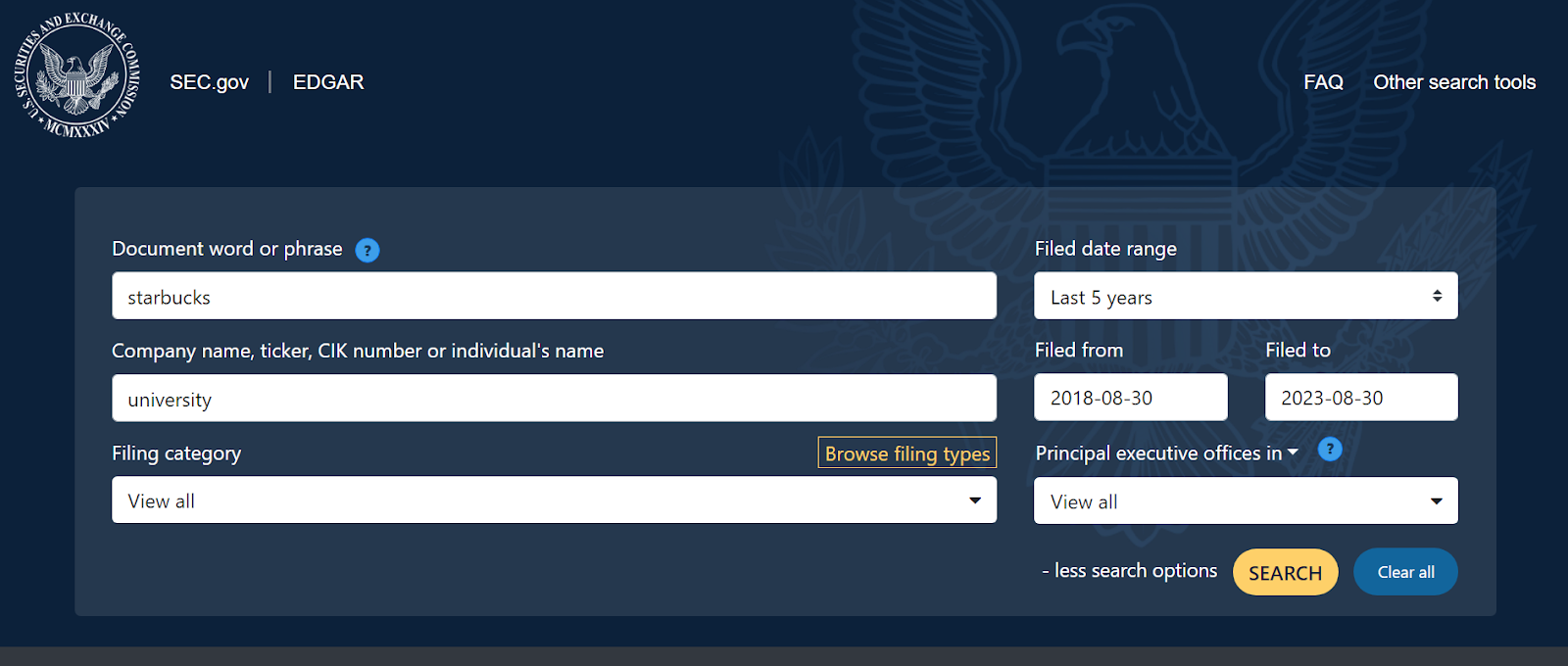

One way is by searching the Securities and Exchanges Commission EDGAR database where some universities disclose some of their stock and mutual fund holdings. For example, let’s click “+ more search options” and type in “university” in the “company name” slot and “Starbucks” in the “document or word phrase” slot, like this:

One result that came showed that Georgetown University very recently disclosed owning 49,957 shares of Starbucks stock, worth nearly $5 million. This information is accessible by clicking on the “FORM 13F INFORMATION TABLE” in Georgetown’s most recent filing that comes up.

Many universities also invest in Starbucks indirectly through mutual funds. These are funds that themselves invest in many different companies, so that by buying shares of mutual funds, you’re in fact buying slices of shares in many corporations all at once.

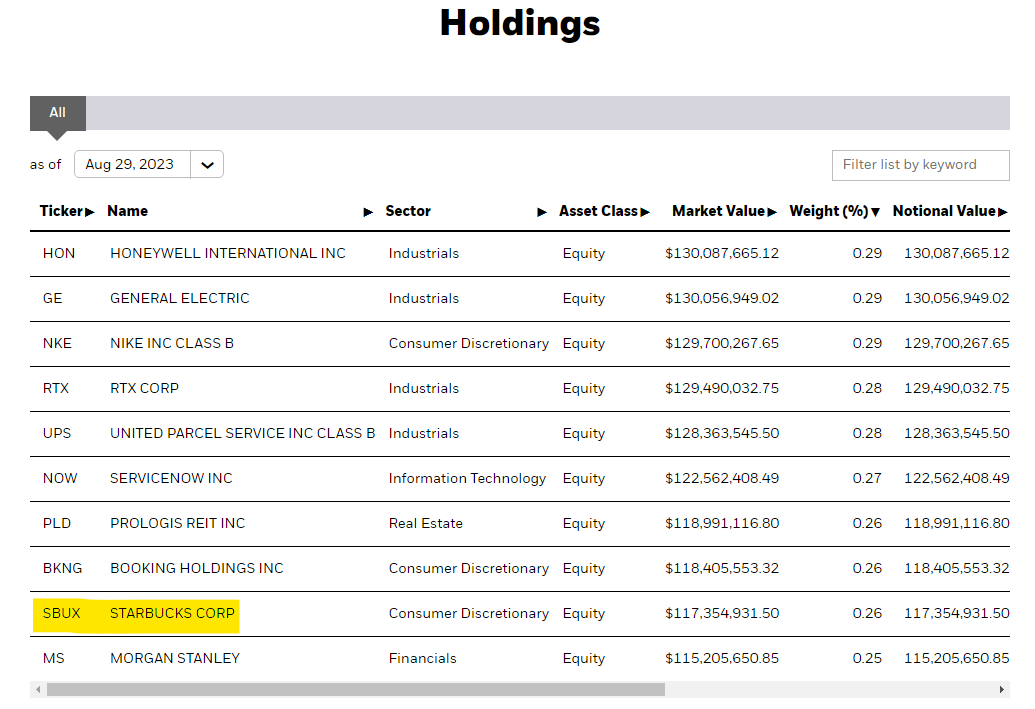

For example, in the SEC EDGAR database, a search of Yale University will reveal a recent holdings report that shows Yale owns 6,564 shares of “ISHARES TR CORE S&P TTL STK,” which is a mutual fund run by the asset manager BlackRock through its iShares division. If you click the “holdings” tab on this fund and scroll through, you’ll see that 0.26% of the fund is made up of investment in Starbucks.

Again, finding clear evidence of your university’s investments in Starbucks or any other company takes a lot of digging, and you might not find anything disclosed. But there’s also a lot of information out there if you know where to look. Moreover, this research can be fun to do, especially collaboratively!

Here is a resource you can use that LittleSis put together that shows, with video tutorials, how to get started in researching university investments through methods described in this post.

Another way many universities disclose financial information, including investments, is through annual 990 forms they must file with the IRS. Propublica has a great Form 990 search tool that you can use.

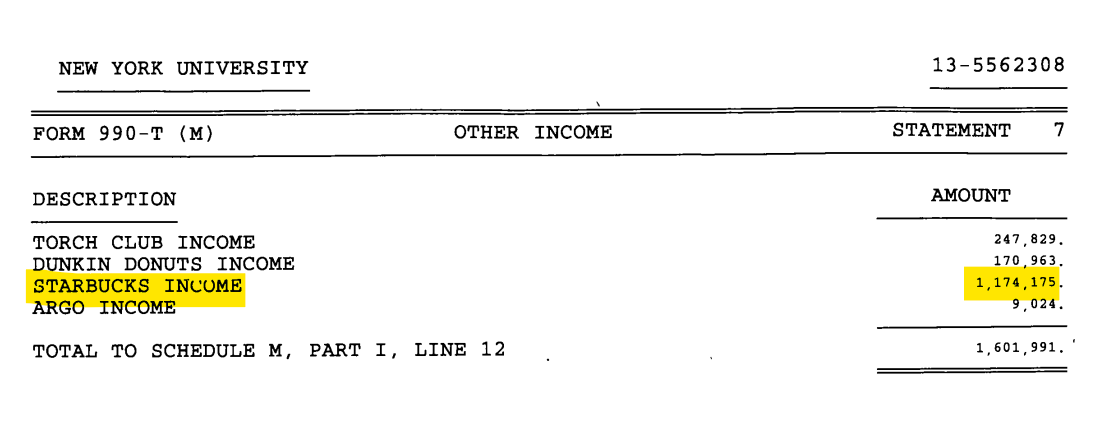

For example, if we search “New York University” and look at their 990-T form from 2020, it shows on page 100 a disclosure of $1,174,175 in “Starbucks Income,” and on page 101 that NYU spent over $700,000 on “Starbucks Expenses.” 990-T forms are good to look at because they report “unrelated business income” from university investment partnerships. They also may include different funds that universities are invested in that may — as discussed above — be invested in Starbucks.

Finally, public universities sometimes publish the holdings of their investment portfolios. The University of California publishes investment reports, including the holdings of its General Endowment Pool that is the UC regents’ “primary investment vehicle for endowed gift funds.” Its holdings include numerous mutual funds that may invest in Starbucks, but moreover, it shows a $154,737,025 invested in a fund called “ARIEL US SMALL CAP,” which is overseen by Ariel Investments, the asset management firm co-run by Starbucks lead independent director, Mellody Hobson, according to both Starbucks’ and Ariel Investments’ websites. A search of the University of Illinois’s investment portfolio leads to annual reports that also show that the university invests with Ariel Investments (here referred to as “Ariel Capital Management”).

Even if your university doesn’t disclose its investments anywhere, it’s important to remember that campus communities can demand transparency around university investments in anti-union companies and also demand that their institution adopt policies forebidding investing in or doing business with companies that the NLRB finds has violated workers’ rights.

“Union Avoidance” Law Firms

Central to Starbucks’ anti-union campaign have been law firms, most notably Littler Mendelson. In exchange for millions of dollars in payments, these law firms advise Starbucks in resisting unionization and carry out its legal work with the NLRB.

Students have found creative ways to protest law firms that represent corporate actors whose business drives injustice. For example, law students came together a few years ago to protest a law firm called Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP (or just “Paul Weiss”) that represents ExxonMobil. At Harvard, Yale, and beyond, students engaged in loud and visible actions against the firm when it visited campus, naming and shaming Paul Weiss for profiting from its defense of a fossil fuel giant.

The goal here wasn’t just to call attention to ways that the firm was facilitating and profiting from climate chaos by representing ExxonMobil, but also to make its name more toxic for the many talented law students who will be looking for work but who also care about climate issues. These protest efforts all converged in a new organization, Law Students for Climate Accountability.

Law students who oppose union-busting could similarly develop a network that makes a list of “union avoidance” law firms and shares information about when they are visiting campuses.

Moreover, while Littler Mendelson is the most prominent “union avoidance” law firm working for Starbucks, you can also identify other law firms that do various kinds of business with the company through searching SEC filings, press releases, and other sources. Some online searching reveals that firms Ogletree Deakins and Jackson Lewis have handled Starbucks labor cases. The law firm Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe counseled Starbucks on its recent corporate bond deal referenced above.

In addition to campus recruitment visits, representatives from Starbucks’ hired law firms sit on some university trustee boards. For example, as of 2022, representatives of Littler Mendelson and Ogletree Deakins sit on the board of on the Georgia State College of Law, and representatives of Littler Mendelson currently sit on the board of the SUNY New Paltz Foundation, Roger Williams University School of Law, and Knox College.

Strategy and Leverage

Students at college campuses are in strategic positions to support labor and social justice campaigns. As long-time labor organizer Stephen Lerner said in a recent interview with scholar and activist Eric Blanc:

“In most universities, you have a large, sympathetic grouping of students capable of winning clear demands through escalating campaigns and dramatic actions. You can start with people wearing the same color shirt one day to support the effort, and over time escalate to things like occupying admin buildings, doing encampments, shutting down campus by blocking the main entrances, you name it. There’s just so much fun, creative disruption that’s possible on campus.”

Corporate power is present at universities in multiple ways — from representation on boards of trustees, to the names of big donors and the names on buildings, to the brands consumed on campus — and all this offers students unique leverage to pressure corporations loudly and visibly, creating embarrassing and undesirable situations for corporate public relations arms.

Moreover, universities are places where you can build coalitions between undergrads, graduate student workers, faculty, and campus workers who work in dining and laundry facilities, maintenance, and other areas. Many graduate students and campus workers are already unionized, and, relevant to the Starbucks fight, may even be affiliated with Starbucks Workers United’s parent union, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

Moreover, many faculty, especially but not only adjunct faculty, experience similar conditions of precarity, low pay, and the degradation of their labor, that Starbucks and other workers in industries like retail, service, and others face. In making these connections, there’s a lot of potential to create lines of solidarity and commonality that puncture the often assumed, but false, barriers between what happens on campus versus what happens off campus.

Campaigns like these build power, consciousness and networks that confront the prerogatives of capital and can also be wielded to counter a higher education regime of student debt, gentrification, hyperpolicing, and attacks on faculty. Moreover, almost any community or labor fight — tenant fights, climate campaigns, racial justice protests — that focus on a corporate actor such as a big landlord, a fossil fuel company, or the companies profiting from policing and mass incarceration, will have hidden-in-plain-sight connections to campus power structures.

Successful labor and social justice struggles against determined corporate giants must involve creating a range of pressure points that can ultimately compel those corporations to back down. Universities have a strategic and helpful role to play in contributing to the build-up of pressure that can ultimately turn the tide on union busters and other corporate actors.